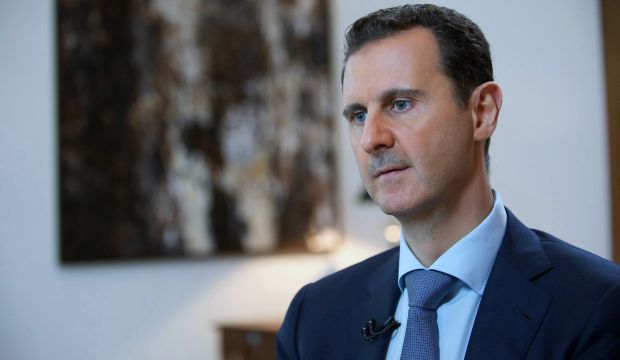

As the Syrian tragedy continues to bleed that nation, a cliché is making the rounds in policymaking circles and think tanks across the globe: There could be no solution without Bashar al-Assad!

We are bombarded with articles urging Western powers to take Assad for an ally to fight the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS).

Until a year ago, the fashionable cliché was different: There could be no solution unless Assad goes!

Shaking a finger in his trademark style and saying, “Make no mistake!” President Barack Obama repeated the “Assad must go!” mantra on more than one occasion.

At the time some of us argued against that cliché. Assad did represent a constituency in Syria and had to be taken into account in the context of a transition that would end in his bowing off stage. To exclude him from the start was a recipe for prolonging the conflict, we argued.

Four years later, we have to argue that the new cliché is equally wrong.

Seeking an alliance with Assad is not only morally wrong but also ineffective as a strategy.

It is morally wrong because Assad is now irretrievably associated with crimes against humanity that no diplomatic double-talk could camouflage.

But even if we discard moral considerations, an alliance with Assad would not make sense in terms of amoral, not to say brutal, Realpolitik either.

Those who urge an alliance with Assad cite the example of Joseph Stalin, the Soviet despot who became an ally of Western democracies against Nazi Germany.

I never liked historical comparisons and like this one even less.

To start with, the Western democracies did not choose Stalin as an ally; he was thrusted upon them by the turn of events.

When the Second World War started Stalin was an ally of Hitler thanks to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. The Soviet Union actively participated in the opening phase of the war by invading Poland from the east as the Germans came in from the West. Before that, Stalin had rendered Hitler a big service by eliminating thousands of Polish army officers in The Katyn massacre.

Between September 1939 and June 1941, when Hitler invaded the Soviet Union, Stalin was an objective ally of Hitler. Stalin switched sides when he had no choice if he wanted to save his skin.

The situation in Syria today is different.

There is no alliance of democracies which, thanks to Obama’s enigmatic behavior, lack any strategy in the Middle East.

Unlike Stalin, Assad has not switched sides if only because there is no side to switch to.

Assad regards ISIS as a tactical ally against other armed opposition groups. This is why Russia is now focusing its air strikes against non-ISIS armed groups opposed to Assad.

More importantly, Assad has none of the things that Stalin had to offer the Allies. To start with Stalin could offer the vast expanse of territory controlled by the Soviet Union and capable of swallowing countless German divisions without belching. Field Marshal von Paulus’ one-million man invasion force was but a drop in the ocean of the Soviet landmass.

In contrast, Assad has no territorial depth to offer. According to the Iranian General Hossein Hamadani, who was killed in Aleppo, Assad is in nominal control of around 20 percent of the country.

Stalin also had an endless supply of cannon fodder, able to ship in millions from the depths of the Urals, Central Asia and Siberia. In contrast, Assad has publicly declared he is running out of soldiers, relying on Hezbollah cannon fodder sent to him by Tehran.

If Assad has managed to hang on to part of Syria, it is partly because he has an air force while his opponents do not.

But even that advantage has been subject to the law of diminishing returns. Four years of bombing defenseless villages and towns has not changed the balance of power in Assad’s favor. This may be why his Russian backers decided to come and do the bombing themselves. Before, the planes were Russian, the pilots Syrian. Now both planes and pilots are Russian, underlining Assad’s increasing irrelevance.

Stalin’s other card, which Assad lacks, consisted of the USSR’s immense natural resources, especially the Azerbaijan oilfields which made sure the Soviet tanks could continue to roll without running out of petrol. Assad in contrast has lost control of Syria’s oilfields and is forced to buy supplies from ISIS or smugglers operating from Turkey.

There are other differences between Stalin then and Assad now.

Adulated as “the Father of the Nation” Stalin had the last word on all issues.

Assad is not in that position. In fact, again according to the late Hamadani in his last interview published by Iranian media, what is left of the Syrian Ba’athist regime is run by a star chamber of shadowy characters who regard Assad as nothing but a figurehead.

The US Secretary of State John Kerry who, as a senator, befriended Assad and his wife, learned that the Syrian dictator was one player among many in the murky world of Damascene power politics.

Moreover, as a result of more than four years of devastation even the “star chamber” may no longer have the power it once possessed. Today, at least part of Syria’s policies is decided not in Damascus but in Moscow and Tehran.

To sum up: Stalin had territory, manpower, natural resources and authority, all of which Assad lacks. The analogy, therefore, won’t stand.

There is one last argument that advocates of alliance with Assad advance: If he goes, there could be a vacuum.

That argument, too, could be challenged.

Why speak of a vacuum rather than a space opening for a new start for Syria?

Regardless of his personal qualities, or lack of them, Assad has become a symbol of what most Syrians do not want. If, and when, he goes, a space will open in which those who do not want him may seek a compromise with those, in dwindling number, who wanted him.