With news from the Middle East dominated by horror stories, little attention has been paid to a small piece of good news from a remote corner of the turbulent region. Earlier this week, the outgoing President of Afghanistan Hamid Karzai bid his fellow countrymen farewell, handing over power to his successor Ashraf Ghani.

Well, you might wonder what the big deal is. The big deal is that this was the first time since the emergence of Afghanistan as a state 300 years ago that the leader of the nation has bowed out without being murdered, forced into exile, or toppled by a civil war, a foreign invasion, or a palace coup.

Karzai is the first Afghan leader to have managed to hang on to power for more than a decade. The last monarch, Muhammad Zahir Shah, effectively held power only between 1964 and 1973 when his cousin Muhammad Daoud deposed him. Also, Karzai’s successor comes to power as a result of elections certified by international observers and, more importantly perhaps, accepted by the loser.

Even a month ago, some observers feared that Afghanistan, true to its checkered history, might yet be plunged into a bloody war of succession. And, to be sure, with all the dark clouds hanging on the horizon, Afghanistan is not yet out of the woods.

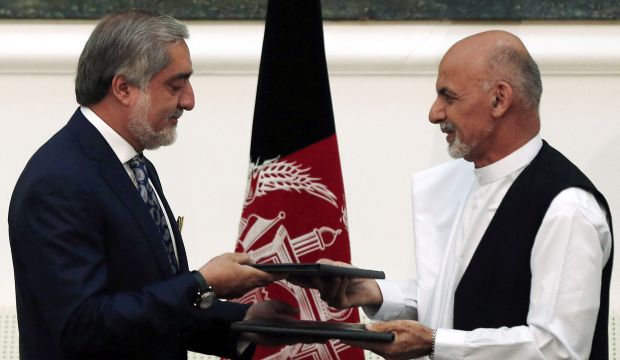

Nevertheless, the new Afghan elite have shown a degree of wisdom and maturity rare in the so-called “developing world,” where compromise is often regarded as a sign of political weakness rather than moral strength. Ghani, the declared winner of the second round of the election, and his challenger Dr. Abdullah, have realized that unless they agree to share power they risk ending up with no power at all.

This happy outcome is due to a number of actors. Some credit must go to Karzai, who refused to take sides and—working behind the scenes—helped the rival camps come together.

My opinion of Karzai has registered many ups and downs. Initially, I regarded Karzai as one of history’s opportunists, one of the men, and sometimes women, who happen to be in the right place at the right time and know how to seize the moment.

After the 9/11 attacks, when Karzai started to play a positive role in forging an alliance of anti-Taliban groups, my view of him improved.

Since this is not an assessment of Karzai’s tenure, it must suffice to note that, today, I think that he did more good than harm, if only by helping produce a relatively smooth transition.

The main credit, of course goes to Ghani and Dr. Abdullah, if only by recognizing their limitations, something that all politicians would benefit from doing. However, just as a single swallow does not a summer make, one item of good news does not guarantee a happily-ever-after scenario for Afghanistan. The power-sharing deal brokered by Ghani and Abdullah remains fundamentally fragile.

In the first place, its fragility stems from its basically extra-constitutional set-up. In most cases, any law is better than no law at all, although it is always wise to apply a legal system with some flexibility.

In the Ghani-Abdullah deal, the president remains head of state with immense constitutional powers. However, the day-to-day running of the government will be in the hands of a prime minister, known as “chief executive” in the deal. This creates some confusion regarding the hierarchy of legitimacy, especially because it is not clear to whom the “chief executive” will be reporting—the parliament or the president? To complicate matters further, Abdullah, who has been named as chief executive, will exercise a major prerogative without holding a constitutional office.

The deal will also be fragile because Ghani and Abdullah will each appoint half the members of the Council of Ministers, creating a two-tier Cabinet. Had this been a formal coalition, the chosen method of power-sharing would not have affected its actual performance. However, the “unity government” is not backed by a parliamentary majority produced as a result of a multiparty coalition.

And there is another problem. Once he is named prime minister, why should the man who is given the post listen to Ghani, who, having played his only card, would not be able to replace him without provoking a crisis? And, if another man is named in his stead, Ghani and Abdullah, the two men who contested the election and won all the votes in the second round, might end up giving actual power to someone who, not being a candidate, received no votes!

After more than a decade, it is clear that the US-style presidential system imposed by the Americans does not accord with Afghanistan’s political realities. In fact, the presidential system, is not working so well in the US either. Afghanistan would do much better with a parliamentary system, reflecting the nation’s ethnic, linguistic and religious diversity through proportional representation.

Much as I hate making predictions—that is the task of fortune-tellers, not journalists—I can’t help feeling that the Ghani-Abdullah deal may not last for more than a year. Thus, the question is how best to spend that year.

I think four major tasks could be tackled. The first is constitutional reform to introduce a parliamentary system within a reasonable time frame. The second is signing the security pact with the US. The third is to make a genuine bid for the normalization of relations with Pakistan. Finally, the new government should seek peace talks with the members of the Taliban that seek inclusion into the new political system rather than dream of destroying it.