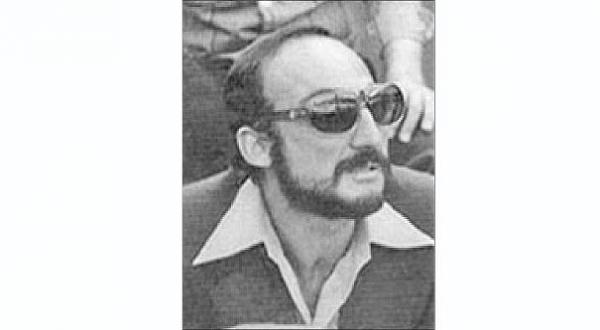

Before the Khomeinist revolution in 1979, Farhad Massoudi was owner, president and chief executive of the Ettelaat Media Group, one of the largest media companies in the world with a dozen dailies, weeklies and monthlies in Persian, Arabic, English and French.

Last week, however, Massoudi died aged 75 after years of exile in Britain, France and eventually Monaco. Remarkably, however, right to the end, he kept his spirits high with his beloved sports and a seemingly endless sense of optimism that he had inherited from his father, Abbas Massoudi who founded the daily Ettelaat 90 years ago and is thus regarded the father of modern journalism in Iran.

Farhad was born in Tehran and, like many children of the Iranian middle classes in the pre-Khomeini era, was educated in Switzerland, Britain and eventually the United States. When he was born, Ettelaat was one of two dozen dailies appearing in a Tehran that was then occupied by Allied forces that imposed strict censorship. Ettelaat then was a cash-starved enterprise managing to hang on thanks to handouts from well-wishers and small ads.

However, by the time Farhad was in his early youth, Ettelaat had already become a money-spinner while his father Abbas had been named a senator and one of the grandees of the establishment.

Farhad never thought of becoming a journalist and, years later when he had already become Ettelaat’s owner and boss he told me that he had dreamt of a sporting career. He partially realised that dream by becoming President of the Iranian National Volleyball Association.

My guess it that Farhad embarked on a journalistic career in obedience to his father who, like traditional fathers everywhere in the Middle East, wanted his eldest son to succeed him in the family business. But even then, Farhad did not have his father’s natural talent as a reporter and hunger for chasing a good news story.

Knowing that, he applied his energies to the managerial side of the enormous empire that his father had created. For a while, Farhad was also forced to take over the paper’s editorship to deal with mounting political pressures on the privately-owned media in the mid to late 1970s. In 1978, his leadership was crucial in restoring part of the paper’s prestige after it had been obliged to publish a fake “letter to the editor” attacking the late Ayatollah Ruhallah Khomeini in gross terms, triggering protests by mullahs in Qom. The Khomeinist terror group Fedayeen Islam controlled by the Ayatollah even threatened Farhad with assassination.

The Ettelaat group won a number of international prizes especially for its French daily Journal de Tehran while its Arabic language weekly Al-Ikhaa (Fraternity) built up a significant leadership base in several Arab countries.

When the mullahs seized power in February 1979, one of their first acts was to confiscate the privately owned media groups, notably Ettelaat and put them under the direct control of the Office of the “Supreme Guide” who appoints the top managers as well as editors.

The last time I met Farhad in London he said he was happy that his father had not lived long enough to see what had happened to Ettelaat and to Iran.

I didn’t tell Farhad this at the time but thought that though Iran’s miseries since the Khomeinist takeover would have broken Abbas Massoudi’s heart, the old warhorse of the Iranian press would have not missed the journalistic potential of the Iranian tragedy as “a damned good story”.