London, Asharq Al-Awsat—“Thank you, press!” That was one of the placards carried by many during the mammoth demonstrations across France last week in a show of support for freedom of expression. Triggered by the brutal assassination of cartoonists from the satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo on January 7, the marches attracted people from all walks of life and all shades of the ideological spectrum.

Nevertheless, the positive sentiment shown towards the press and the media in general must have surprised more than one observer. For, according to opinion polls, journalists have been among the most unpopular people in France, even behind estate agents, for more than a decade. So, are we witnessing a change in the largely negative image of journalists and the media in general? The change in sentiment may be partly due to the fact that humans often discover that, when all is said and done, they begin to appreciate what they feel they may be about to lose. One could complain about press freedom but end up defending it tooth and nail when it is threatened.

The question is whether this sudden surge of love for the press will help it transcend the many economic, technological, and social problems that threaten at least part of it with extinction. During the past 10 years almost a quarter of the printed press has either disappeared or been forced to reduce its pagination. With one or two exceptions, virtually no French newspaper or magazine could have survived without direct and indirect subsidies from the government. All but four of the nation’s daily newspapers have been on the verge of bankruptcy for years.

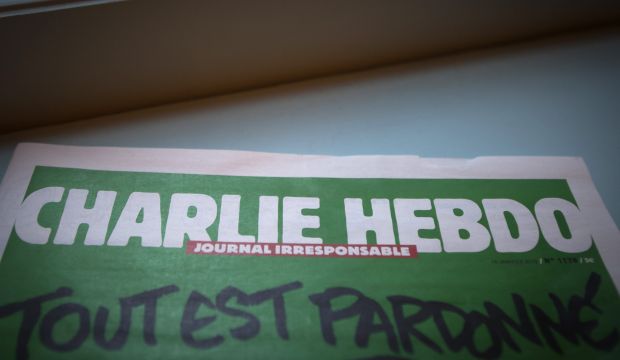

The now iconic Charlie Hebdo itself was on the edge of closing down when the jihadist attack came. The number of its subscribers had fallen to under 10,000, the lowest in years, while even the best print-run did not exceed 60,000. Last Wednesday, however, the weekly’s post-attack issue sold 1.5 million copies within hours. At the time of this writing, the weekly’s provisional managers were talking of printing 5 million more copies. Income from that single issue could ensure Charlie’s survival for at least another two years.

The surge in public interest has also benefited other publications. Newspaper circulations rose by an average of 30 percent during the emotionally charged week, giving some moribund dailies and weeklies a well-timed shot in the arm.

The attack on Charlie Hebdo could certainly not be labeled as a “clash of civilizations” as some have suggested. But it does indicate the failure of some people, including jihadists of French nationality, to understand the deeper layers of the French culture.

The French love thumbing their nose at authority, be it religious, political or in the business world. They love caricatures, comedians, and provocateurs who specialize in lampooning the great and the good, the powerful and the pretentious. The very word “caricature,” now adopted by almost all languages across the globe, comes from the French. As far as I know, France is perhaps the only country where caricatures appear in every newspaper and, more importantly, on many front pages. It is also the only country where cartoonists and satirists can achieve stardom. Everyone knew who Georges Wolinski and François Cavanna were. Charlie’s Editor Stéphane Charbonnier, known as “Charb,” was a star figure although very few people bought his magazine. Le Monde’s front-page cartoonist Jean Plantureux, or “Plantu,” is easily the best-known member of the daily’s editorial staff.

France is also exceptional in other ways. It is the only country where every news bulletin on major radio stations includes a comedian hired to make fun of newsmakers and events. Major television channels bring in cartoonists to draw unflattering caricatures of the great and powerful as they are being interviewed live.

Apart from Japan, no other nation buys as many albums of comic strips as France does. Everyone has heard of Tintin and Asterix as iconic French figures. Also, since 1974 the largest annual festival of cartoons and comic strips has been held in the French city of Angoulême.

All that is not surprising; satire has always been a major ingredient of French literature and culture in general.

Such giants as Rabelais, Beaumarchais and Molière are high up in the Pantheon of French literature. Rabelais’ slogan, “Do what you like,” included saying what one liked. Thus no one was spared being lampooned, no one including guardians of any temple, servants of any palace, and wielders of any swords.

The very French school of “boulevard” comedy reflects the nation’s taste for irreverence and provocation with people like Georges Feydeau and Eugene Labiche, among many others, tackling all sorts of social, political and religious taboos.

Satire is also a key theme in many works of high-level French literature. Voltaire is a master of satire, or at least the tongue-in-cheek variety. Diderot’s Jacques the Fatalist is a masterpiece of comic writing. Even Victor Hugo, the most stiff-necked of French writers, allowed himself moments of satirical diversion, even in such tragic works as The Man Who Laughs.

That there was always a market for humor and satire in France is indicated by the fact that a whole theater was devoted to it in Paris, the Opéra-Comique, where works of light-hearted music, notably by Jacques Offenbach, drew in huge crowds. One finds theaters and cabarets offering stand-up comedy in almost every French city.

Like today’s jihadists, Napoleon hated cartoonists, partly because they insisted on depicting him as a midget. But even he did not dare order their murder. He asserted that “four newspapers are more dangerous than 4,000 muskets,” but knew how far he could go in muzzling the press. Napoleon’s nephew, Louis Bonaparte, the self-styled Emperor, shared his uncle’s horror of caricaturists, especially when cartoonists made fun of his rather ridiculous goatee.

The French often flatter themselves for their sense of humor and poke fun at their German neighbors for their alleged stiffness. Some French also think that Algerians lack a sense of humor. However, though of Algerian origin, the Kouachi brothers, who had never been to Algeria, may have been exceptions. In 1994, in the middle of the mayhem caused by jihadists in Algeria, I attended an annual festival of laughter in Oran where, to my surprise, I discovered that Algerians could be as funnily irreverent as their former French rulers, if not more. The tragic events of Paris indicate a clash of cultures but do not shut all doors for dialogue and understanding. While the latest issue of Charlie Hebdo was selling like hot cakes, Voltaire was topping the list of best-selling books with his Treatise on Tolerance.