“It was as if a stranger sang through my soul,” wrote Azraqi Hervai, an 11th century Persian poet. “But, then, I realized that it was my own lost voice, coming back to me.”

Maybe because it was originally meant to be recited or sang aloud, poetry has always been about the voice. As Rilke

noted you don’t become a poet until you have found your own voice. After that, what counts is the song not the singer.

But to find his voice the poet first has to listen to others, an enterprise that could land him in a confusing cacophony or help him find his own voice. In the same century as Azraqi, The great Persian poet Manuchehri of Damghan, spent years “listening” to pre-Islamic Arab poets – many of whom are now all but forgotten. That helped him find his own voice that comes to us in some of the greatest qasidas ever written in Persian.

Listening to the voice of other poets for inspiration was a common practice for classical Arab and Persian poets who wove echoes, far and near, into their own voice. One technique was known as “welcoming” or “istiqbal” in Arabic in which the poet takes a line or a whole theme from another poet and creates a new qasida or ghazal. One of the best loved ghazals of Hafez of Shiraz starts with a “welcome” hemistich borrowed from the Umayyad Caliph Yazid Ibn Muawyyiah.

Another technique was “iqtibas”, meaning “taking the torch in the darkness” through which the poet imitates another poet, adding his own touches to create a slightly different voice.

Western poetry had its own techniques for what one might call “borrowing voices.” After all, though writing in Latin, Virgil and Ovid retained heavy Greek accents. The Victorian English poets, in turn, relayed echoes of Latin poetry through deliberate or unconscious imitations.

In modern times and with the emergence of a polyglot world, the aspiring poet has access to virtually endless voices. The American poet Robert Lowell learned to listen to poetical voices in a dozen languages, echoing them through recreations in his” Imitations”, a delightful collection of verse. In it he “welcomes” poets as diverse as Homer and Leopardi.

In the past century or so the Arab poet has had access to poetic voices from the outside, mostly Europe and more especially France, England and Germany. However, in most cases those voices reached episodically and, often, through the filter of not always perfect translation.

However, from the middle of the last century, a combination of circumstances has led to more direct contact between Arab poets and poetical voices in other parts of the world. A large number of Arab poets have found themselves in exile, cut from their native linguistic roots and plunged into daily diglossia with its dangers and promises.

In some cases, the avalanche of new voices, exotic and seductive, has buried the Arab poet’s own voice. In some case, the Arab poet in exile even lost imaginal contact with his own cultural topos, reflecting his enforced abode often in primary colours. Many Arab poets I have read who write about frozen forests that remind me of Sweden, and spaghetti-like motorways that recall California.

Then there are those who are so overwhelmed by the foreign voice that they post their own voice. At times you feel as if it is Saint John Perse, to cite just one example, who is speaking through the Arab poet, albeit a Saint John Perse suffering from a heavy cold.

The beauty of poetry is that, being the key to freedom of imagination, it recognizes no fences unlike religion that is all about erecting fences and imposing exclusions. Poetry is the most efficient tool of cultural exchange because it allows friendly visits, again unlike religion which, even when it accepts dialogue limits itself to shouting its shibboleths across the fence.

The reason is that it is quite possible to live in several cultures, even if at times it means as visitors or exiles while it is not possible to have more than one religion at the same time. One could speak or even think in several languages while the baroque chiaroscuro of religion permits no diversity.

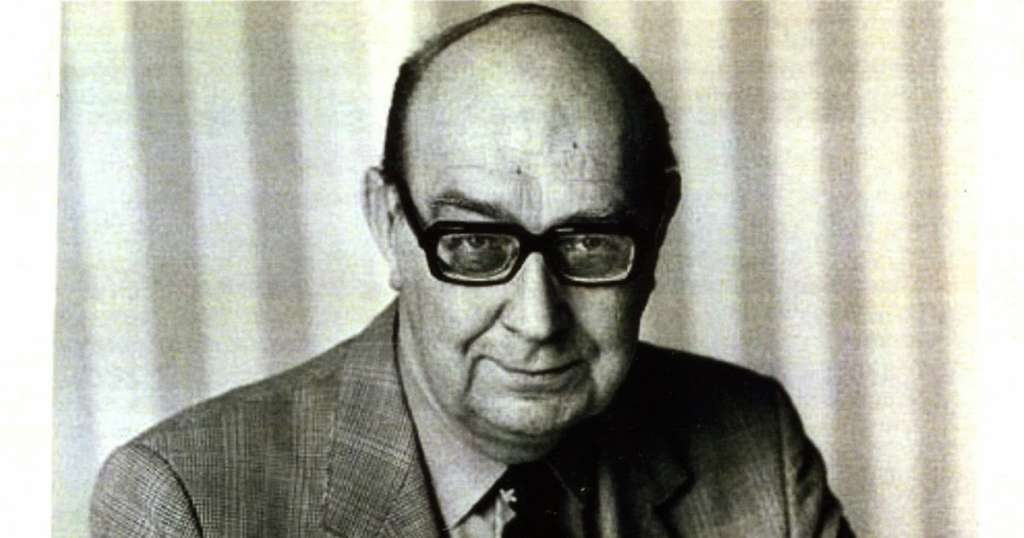

Thus, at least for me, the first test of a poet’s success is whether or not he or she has found a voice of his or her own. In that sense, I think Fadel Assultani has succeeded. I have been reading his poems, on and off, for more than a decade, witnessing the emergence of his voice, initially no more than a tentative murmur, to how it reached the right pitch and tone.

Without any braggadocio of the kind that Arab poets favour, Assultani simply ditched most of the anathemas and interdicts designed to keep Arab poetry frozen at some point in the distant past.

Perhaps without knowing it, Assultani took the advice of the great Sufi master Roumi to “grasp the kernel and throw the shell to donkeys.”

Roumi also regarded metres and rhymes as “trifles not to be bothered about.” In one poem he cries out: “mufatilan muftalian (one of the nine principal Arabic and Persian metres) is suffocating me!” Poetry isn’t concerned about trifles as the Latin adage has it about law: De minimis non curat praetor!

This collection of Assultani’s poems provides the reader with an opportunity to hear the full tonality of his voice, something that reading a single poem might not accomplish. Assultani’s style is closer to chamber music than to symphonic exposition. His voice is intimate, often mournful and always sincerely measured. Like Manuchehri or Lowell he is in a dialogue with many poets, from T.S. Eliot and Philip Larkin, perhaps his favourite English poet, to Paul Eluard and Jacques Prevert with many classical Arab poets, not to mention the poet who wrote Gilgamesh, maintaining a presence.

One of Assultani’s favourite themes is that of “elswehereness”, living in one reality physically and in another reality spiritually. His is not the classical case of nostalgia, the opiate of the beaten in history, as expressed by many poets in exile. For Assultani what matters is to live his “elsewhereness”, not lament it.

It is impossible to read Assultani without sharing the immense grief he expresses in his poems. This is all the more effective because there is no chest-beating hyperbole about the treachery of destiny, a theme of so much classical Arabic poetry. Here, the words are certainly Arabic, and rich in that context, but the sentiment is cold and clinical, very English if you like, making it all the more devastating.

Assultani has found his voice, and speaks in the universal language of poetry, albeit with an Iraqi accent, perhaps even an accent from Sidrat al-Hindiyah. END