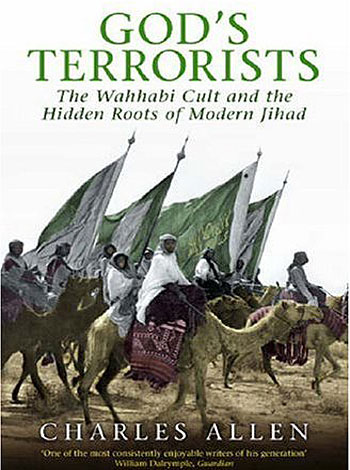

God’s Terrorists

The bigger bookshops have always offered browsers a helping hand by presenting new books in sections based on themes. For example, if you are looking for poems you look for the section “Poetry” while lovers of detective stories head for the section named “Crime”.

It is, perhaps, time to add a new section for “Terrorism”. For the 9/11 attack against New York and Washington has generated a veritable industry that churns out thousands of books on terrorism each year. Most of these are not worth the paper they are printed on. Some are vicious in the sense that they seek to provoke a “clash of civilisations” by fomenting religious hatred.

The fashion of writing instant-coffee style books on terrorism has had another pernicious effect. It has put writers, especially historians, under pressure to “arrange” their work to reflect current assumptions, presumptions, and prejudices.

This seems to be what happened to Charles Allen, a reputable historian of British colonial rule in India with direct family experience of the Raj.

Allen’s new book “God’s Terrorists” seems to have started as a regular study of the rebel movements that challenged British presence in India, sparkling armed conflicts and even full-scale wars. Very quickly, however, the book seems to have been put on another trajectory with the aim of transforming those rebel movements into terrorist organisations which, in turn, are supposed to be the political ancestors of characters such as Abu-Mussab al-Zarqawi and Osama bin Laden.

Allen also succumbs to another fashionable idea among the writers of instant-coffee books: describing all radical Islamist groups as “ Wahhabi.”

Claiming that he has found “ the hidden roots of modern Jihad”, Allen tries to establish a link between the various anti-British Indian rebels and the teachings of Muhammad Ibn Abdul-Wahhab. But it soon becomes clear that Allen has no knowledge of those teachings beyond what he has read in books written by equally uninformed fellow “experts” in terrorism.

For example, Allen claims that the Wahhabis made a certain Akbar Shah the King of Swat because he was a “sayyed” and thus a descendant of the Prophet. Now anyone familiar with the teachings of Muhammad Ibn Abdul-Wahhab would be aware of his rejection of any distinction among believers based on blood and descent.

Most of the Muslim rebellions against the British in India were of Mahdist inspiration, as illustrated by the myths of “ the King of the West”, “ The Awaited One” ( Al-Muntazar), and the projected joint journey of the Mahdi and Jesus to Jerusalem where they will kill the dragon.

The rebellions also had strong Sufist colourings as illustrated by the use of such terms as Pir, Murshid, Murad, Murid, and Zawiyyah. In fact, Allen himself reports on the role played by Sufi fraternities, notably the Naqshbandi, in most of the rebellions.

Now anyone who knows anything about the Wahhabi teaching would know that it does not include any love for Sufism and Sufis.

Because he is unable to cite evidence that the anti-British rebels were Wahhabis, Allen falls back on spurious suppositions. For example, writing about one rebel group he says: “The presumption must be that some were Wahhabis.” But Allen does not say what that presumption is based on. Nor do we learn what he means by “some.” About another rebel group he writes: “They were afterwards named as Wahhabis and the charge may well have had some truth in it.” Really? Who named them? On what grounds? And how much is “some truth”? Allen does not say. Elsewhere he says a certain Indian Muslim rebel leader had been in Medina “almost at the same time” as Muhammad Ibn Abdul-Wahhab, and adds that “they are likely to have met.” But can anyone take this sort of assertion as serious historic research?

A good part of the book deals with the successive rebellions in Swat, in the uplands of what is now Pakistan’s semi-autonomous Tribal Area. Swat served as the core of the Sepoy revolt, the largest and most serious uprising against British rule. Sepoys were native Indian troops enlisted in the army of the Raj and commanded by British officers. (The word Sepoy is from Persian Sepahi which means soldier).

Allen offers a moving account of the famous revolt, albeit from the point of view of someone nostalgic about the Raj. He runs into trouble, however, when he tries to portray that anti-colonial struggle as “an Islamist terrorist” enterprise. Fortunately, facts that he cannot ignore hit back. He is forced to admit that in the Swat revolt “a majority of the Sepoys were high caste Hindus.” He also notes that Pir Ali of Patna, who led another major revolt “failed to win the Wahhabis over to his cause.”

Allen suffers from the problem that quite a few other writers about the Muslim world have encountered. In Islam, at least until the middle of the last century, no political movement could achieve public expression without assuming a religious persona. But this does not mean that those political movements could or should be studied as religious phenomena.

Indian Muslims who wished to get rid of British rule could not have fought the Raj in the name of secular ideologies that they did not know at the time. But the fact that non-Muslims, especially “high caste Hindus” joined the Muslim-led revolts showed that Indians of whatever faith knew that the fight was political not religious.

Another assumption made by Allen is that anyone who fought against Western imperial powers was a “terrorist”. But all the clashes and wars that he writes about can be seen as regular military encounters rather than instances of terrorism. Terrorism has a precise definition which Allen ignores because he believes that “ anyone who is not with us is a terrorist.”

A more recent example may help illustrate the point.

Mullah Muhammad Omar, the leader of the Taliban, for example, cannot be described as a terrorist although he was a despotic ruler who led Afghanistan into tragedy. Omar won his victories against his rivals either by bribing them or killing them in regular combat. He never planted a bomb in a pizza shop with the aim of killing innocent people. Nor did he send minions on suicide missions designed to kill people who were not involved in any conflict with him.

Osama bin Laden, however, could be described as a terrorist precisely because he has done all of what Omar did not do.

Some of the Indian rebels that Allen writes about were closer to Mullah Omar than to bin Laden. They were religious fanatics but not terrorists.

Allen’s book suffers from the recent decline in editing standards in British publishing and is marred by errors.

He writes the word Sayyed in three different ways, at times on the same page.

Feroz, a claimant to the crown of Delhi, is alternately presented as a nephew, a son and a cousin of Bahadur Shah, the last Mughal Emperor.

Fereydoun becomes “ a prophet of ancient Persia” rather than the mythical king that he was.

The word Fakir is translated as “saint” rather than “ humble” or “ poor” which are its true meanings.

The word Sardar means “ chief” and not “ bare-headed” as Allen thinks.

The Al Aqsa Mosque is in Jerusalem and not in Cairo, as Allen keeps saying throughout the book.

The Salafi movement, shaped in the Middle East, especially Egypt, was not an invention of the Deobandi School in India, as Allen believes. To describe the Deobandi movement as a fanatical movement and a breeding ground for terrorism is untrue and unfair.

The Grand Mufti of Palestine was Haj Amin al-Hussaini not Muhammad Hussain.

Sultan Mahmoud Ghaznavi’s title “ Ghazi “ means “ warrior for the faith”: not “ butcher” as Allen claims.

“Risalat al-Jihad” means ( Epistle on Jihad) not “ The Army of Holy War” as Allen claims.

The title of akhund, a Turkish-Persian term, designates a religious teacher who is equal in rank to a colonel in the army. (Agha-Khandeh). It does not mean ” saint” as Allen tells us, especially because in Islam there are no saints as in Christianity.

For obvious reasons, Mullah Omar and bin Laden could not have been pupils at a Deobandi school in Pakistan in 1989.

Allen states categorically that Ayman al-Zawahiri, an Egyptian associate of bin Laden, was behind the assassination of Abdullah Azzam a Palestinian-Saudi militant who served as ideological guru to the “ Arab Afghans” in Pakistan. But Allen cites no evidence for this charge.

Although the book’s title is an insult to millions of Indians, Muslim and Hindu, who fought against foreign domination, Allen’s work should be welcomed by Muslim readers. It helps them learn more about the relationship between Islam and the Raj at a time that Great Britain was the largest “ Muslim empire” in history in terms of the number of Muslims who under its rule.