Khomeini, de Sade, and Me

By Abnousse Shalmani Grasset, 177 pages Paris, 2014

If we are to believe Abnousse Shalmani, being a woman is hard work even in Western democracies boasting of gender equality and human rights. It is even harder in contemporary Iran where a sectarian regime rejects the concept of individual freedom even for men let alone women.

Born in Tehran in 1977, two years before the Mullahs seized power, Ms. Shalmani was faced with “the precarious nature” of her existence when, aged seven, she was first sent to school.

She found the rite of passage terrifying.

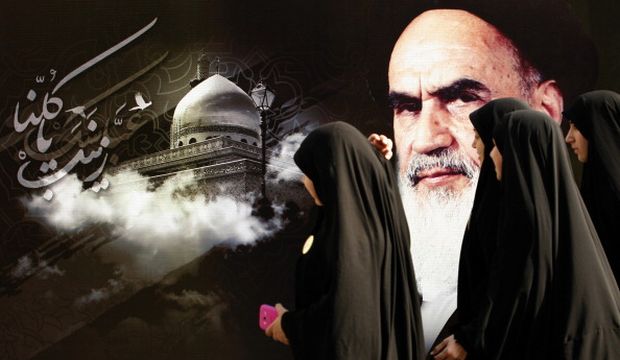

Suddenly, she had to wear special clothes, cover her head, and wipe the smile off her face. She was advised to look grim and as ugly as possible. Looking in the mirror, she felt she now looked like a raven. On the way to school she began to notice that there were countless ravens, women wearing the dress imposed by Ruhollah Khomeini, the dour-faced octogenarian Ayatollah who marketed himself as the sole authority on right and wrong.

So, one day, having suffered and cried in secret for weeks in and out of school, the seven-year-old Abnousse simply lost her nerve. She decided to cast away her Khomeinist clothes and run around the school courtyard naked.

You could imagine the scandal, and the dangers that such behavior posed for her parents. While her mother tried to reason with her, urging a secular form of taqiyah (dissimulation), Abnousse’s father decided that the only way to save her was for the whole family to leave the Islamic Republic. The Shalmanis ended up in the French capital in 1985 at a time when many in the West regarded the Khomeinist regime as the epitome of evil.

Abnousse’s mother tried to protect the family by claiming to their French neighbors that they were Armenians. Abnousse’s father, however, insisted on advertising their Iranian identity with the argument that it was Khomeini and his cohorts who had discarded Iranian-ness in favour of an invented Islamist–revolutionary identity.

Shalmani’s book is a mixture of autobiography, literary, and philosophical musings, and novelistic anecdotes narrated with passion and humor.

Once in Paris, Shalmani decided to devote her life to fighting Khomeinism.

In time, perhaps without being conscious of it at first, she started doing this by looking for those who represented the extreme opposite of Khomeini’s worldview. If Khomeini was obsessed with forbidding this and that, Shalmani looked for someone who allowed every excess in human behavior.

She found a point of entry in European, especially French, erotic literature. La Merteuil, the manipulative heroine of Les Liaisons dangereuses became a role model, while Pierre Louÿs’ femmes fatales offered glimpses into a world of freedom through defiance.

Interestingly, Shalmani does not know that Iran itself has a huge wealth of erotic literature, starting with the One Thousand and One Nights right up to Sadreddin Elahi’s novel of the 1950s Our City Blonde, in which a ruthless beauty plays with powerful men of the world like so many pathetic puppets.

French erotic literature is a slippery slope that leads Shalmani to the Marquis de Sade, the 19th-century aristocrat and novelist who died of syphilis in a lunatic asylum.

Shalmani adores de Sade because he forbids forbidding. For him whatever human beings do, including the worst deviations from moral and ethical norms such as incest, must be accepted.

Shalmani thinks that because he permits all, de Sade is the antithesis of Khomeini, who forbids everything. In reality, however, Khomeini and de Sade are two faces of the same coin. Khomeini likes to dissolve women into nothingness by dressing them beyond recognition. In contrast, de Sade transforms women into naked mannequins by undressing them. His heroines, Justine and Juliette in particular, are one-dimensional caricatures of women caught between sadism and masochism.

(Incidentally, Pierre Loti may have hit the point when he said: “Dressing up a woman could be more erotic than undressing her!”)

Unwittingly, Shalmani exposes the amazing sameness of de Sade and Khomeini.

Both men write passionate but ultimately empty prose. Khomeini hides too much, de Sade reveals more than is necessary for good taste. Both are too earnest, devoid of irony, and lacking a sense of humor. Their style could be described as heavy-handed lightness. Khomeini’s uses violence, even torture, to impose his version of virtue. De Sade uses the same methods to impose his version of vice.

For reasons that are hard to fathom, Shalmani thinks that European, especially French, literature and cinema treat women better than Iranian literature and Islamic culture in general. This is not always the case. Women get a poor deal on both sides of the divide, if only because literature reflects the abiding anti-woman prejudice built into the very DNA of most cultures.

Manon Lescaut, the heroine of Abbé Prévost’s novel, and the various mistresses of Diderot’s hero Jacques le Fataliste and Émile Zola’s Nana and L’Assommoir, all get a rough deal, not to mention François Mauriac’s Thérèse Desqueyroux. Kathleen Winsor’s Amber St. Clare (from Forever Amber) does assert her claim to a place in a male-dominated world but only after untold sufferings. John Cleland’s eponymous Fanny Hill is a resourceful whore but ends up more of a victim. Lola Montez has men dancing to her tune but only for as long as she is young and sexually attractive. And Mata Hari, another “strong, self-contained” woman, ends up in front of a firing squad.

In some Hollywood movies—Joan Crawford’s Mildred Pierce, for example—women take control of their destiny and succeed, up to a point, before being brought down and destroyed. In Double Indemnity, Barbara Stanwyck’s character is certainly a strong woman, but she is also a murderer.

Looking for “liberated women,” Shalmani goes on to admire the Japanese geishas, the medieval European courtesans, and even “hermaphrodite types” like Colette and Virginia Woolf.

Shalmani is rightly angry at the Khomeinist belief that women should be “kept covered, controlled, and pregnant” so that they won’t cause mischief. But she fails to see an echo of that same mentality in the German dictum, “For women: children, kitchen, and church.”

Because of her hatred for Khomeini’s treatment of women, Shalmani even goes on to imply that the maternal instinct is an invention of men to keep women on a tight leash. Needless to say, that instinct and its corollary, paternal instinct, are easily observable in most human beings.

Shalmani’s adoration of some iconic figures of Western culture, Voltaire for example, is naïve, to say the least. To be sure, Voltaire was a major philosopher and a passable writer. But he was also full of disdain for women, and hatred for Muslims, Jews, and homosexuals. He was also on the payroll of Russian Empress Catherine the Great.

The point is that one’s dislike of a man like Khomeini should not make one forget that real life isn’t black or white but proceeds in the chiaroscuro of our cultural habitat at any given time.

Allowing one’s life to be dictated by hatred for Khomeini, or Hitler or Stalin or Saddam Hussein or any other monster, is to give them a victory they do not deserve.

It is possible to have a good love life without Khomeini or de Sade or erotic literature, or indeed any literature.

I also feel sorry that Shalmani’s experience under Khomeini has left her with deep bitterness about Iran itself. (She says she even hates pomegranate juice because it reminds her of Iran!) Well, that’s her choice: the bird chooses its tree; the tree never chooses its bird.

Anxious to put as much distance as possible between herself and Iran, Shalmani praises the French Revolution but condemns the Iranian one. However, the truth is that all revolutions are prompted by human failure leading to greater tragedies.

Shalmani’s narrative is at its best when she writes about the wretchedness of exile with its petty problems and big lies, and its false hopes and real disappointments.

Khomeini, de Sade, and Me has already been translated in Italian, Dutch, and German.

It merits being translated into other languages also.