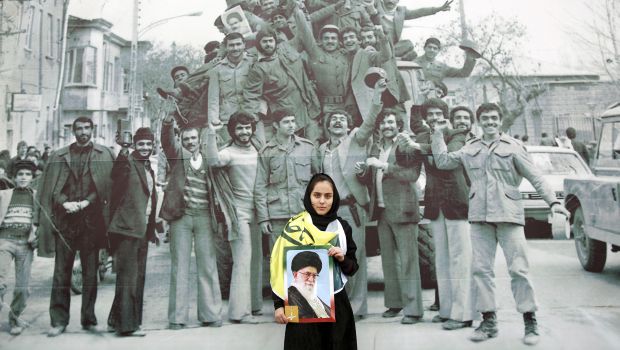

An Iranian woman holds a poster of Ayatollah Khamenei as she poses for a photo in front of an undated 1979 banner photo showing people celebrating the Islamic revolution in Tehran, Iran, on Tuesday, February 11, 2014. (AP Photo/Ebrahim Noroozi)

In his poem Hanzal (The Bitter Fruit), Manuchehr Yektai picks juicy, shining plums and shares them with his young son. As he eats the fruit, however, he realizes that it is getting more and more bitter. Soon, he feels that this is the forbidden fruit that will end up killing him. His son also senses the bitter taste and spits the fruit out of his mouth, splashing its red juice on his white shirt. Yektai’s forbidden fruit is the revolution that generations of Iranian poets dreamed of and wrote about. It is too late for his generation to spit the deadly fruit out. But the young son, part of the future generation, could save himself by doing just that.

Yektai is one of four contemporary Iranian poets to have been nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature. Now in his late 80s he lives in exile in New York, where he is best known as a modernist painter.

His was the second generation of Iranian poets to be seduced—or who seduced themselves—by the idea of revolution imported from France via Russia in the 19th century. At that time there wasn’t even a word for revolution in Persian, so in the early 20th century the poet Iraj Mirza Jalali suggested enqelab, an Arabic word that means “stormy weather” in Persian and “coup” in Arabic. By the 1940s, it was a must for a poet to be enqelabi, revolutionary. This was to have a devastating effect on Iran for two reasons.

First, Iran is one of few countries where poetry has a mass following, the others are Russia and, to a lesser extent, England. In Iran, poets become celebrities; some are even more famous than movie stars. Often, public poetry recitals draw thousands of people. Until the 1950s the position of Malek Al-Shuaara (King of Poets) was one of the most coveted slots in the national leadership. The average educated Iranian knows thousands of lines of poetry by heart, while ordinary folk listen to poems being read aloud and performed in tea-houses, caravanserais and bazaars. Thus, when poets went revolutionary, the bug they had caught was bound to spread throughout society. In other words, poetry made the idea of revolution both legitimate and desirable. By the mid-1970s many significant Iranian poets, among them some of my close friends, had become revolutionaries—major exceptions included Sohrab Sepehri, Fereidun Rahnema, Nader Naderpour, and Sharafeddin Khorassani.

Our revolutionary poets had only a vague idea of what an Iranian revolution led by mullahs might mean. They had a romantic vision of revolution as the dawn of a new era in which people would be happy, free and prosperous. Women would be beautiful and elegant and equal, and people would sing and dance in city squares. Nobody imagined a revolution with beards, turbans and hijabs.

The second reason why our poets’ revolutionary delusion was highly damaging was that they created the impression that when it came to profound socio-political transformations, things would be easy. It was enough for individuals to become “we,” as Hamid Mussadeq suggested, for Iran to build a paradise on earth. Nemat Mirzazadeh sang the praises of “the coming imam” who would trigger a new era of freedom and prosperity merely by wanting it.

Very soon, however, most poets, equipped with powerful social antennae, realized that a revolution that brought mullahs to power could not be about increasing individual and group freedoms. It could only be about reducing those freedoms until they fitted into a pre-established framework of irrational metaphysical prescriptions.

Ahmad Shamlu wrote his famous poem denouncing the Khomeinist system of terror only months after the mullahs had seized power. In it, he lamented the fact that “canaries were grilled as kebab” to silence their song, a response to Khomeini’s ban on music that remains in place 35 years later. Naderpour, a counter-revolutionary from the start, denounced the new regime as rule by Ahriman, a devil-like figure in Iranian mythology. Simin Behbahani, an early enthusiast of “the revolution,” soon aired her deep disappointment in a series of ghazals (sonnets) that propelled her to the position of greatest living Iranian poet.

By the 1990s, with few exceptions, all leading Iranian poets had turned against the Khomeinist regime. To my eternal regret, among those who did not were two old friends Tahereh Saffarzadeh and Mehrdad Avesta. Other friends, notably Mehdi Akhavan and Muhammad Qahreman, tried to temporize. Both included among their fans one Ali Khamenei, who was to become the “Supreme Guide.” That helped them avoid prison and forced exile, and allowed them to get some of their poems published.

For many others prison or exile, or being banned from publishing their work, remained the inevitable fate. Hushang Ebtehaj, probably Iran’s greatest ghazal writer of the 20th century, Siavash Kasra’i, “the poet of the proletariat,” Yadallah Royai, father of Persian surrealist poetry and, of course, Naderpour, Yektai, Zhaleh Isfahani and Lobat Vala—all of them had to take the path of exile. Under former presidents Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani and Seyyed Mohammad Khatami, the Khomeinist regime imposed a system of licensing for publication, under which even classical Persian poets were subjected to draconian censorship.

To silence the poets, the regime used a mixture of bribery, flattery, execution and outright murder. The latest series of executions and arrests have hit a new generation of poets, with ethnic and linguistic minorities as special targets.

However, despite the crackdown launched under President Hassan Rouhani, Iranian poets both inside the country and in exile maintain a surprisingly large audience. Poems by Esmail Khoi, Muhammad Jalali, Reza Maqsadi, and Iran’s most popular living satirist, Hadi Khorsandi, are read in Iran in samizdat editions or in books and magazines smuggled from abroad. The executions earlier this month of Hashem Shaabani, an Arab–Iranian poet from Ahvaz, and Khosrow Barahui, an Iranian–Baluch poet, as well as the disappearance of Hassan Fumani, a poet from Gilan, underline the new crackdown under Rouhani. But they also indicate the fact that poetry remains a weapon in the struggle against a repressive regime.