The Assassins’ Gate: America in Iraq

When the US-led coalition army moved into Iraq three years ago, few expected it to achieve its military objectives in three weeks. Even the advocates of the ”cakewalk” theory had forecast months of bitter fighting before the Ba’athist regime, well-entrenched as it seemed after decades of exclusive rule, could be brought down. The optimists were not the only ones to be proven wrong, however. The past three years have proved the pessimists wrong as well. They had expected a tsunami of refugees fleeing into neighbouring countries while Saddam’s “fedayeen” used chemical weapons against both the invaders and the civilian population.

It is this mixed picture that George Packer, a staff writer for the New Yorker, has set out to capture in this informative and entertaining book. In the process he has shown that there were, in fact, several Iraq wars from the beginning. One was waged within the Bush administration with an intensity that might surprise non-Americans. It made decision-making difficult or impossible, and prevented the emergence of a coherent American strategy. The other war was fought between the administration and those who disliked President George W Bush for a variety of reasons. ( To some extent the same was true of Prime Minister Tony Blair in Britain). Finally, there was the war inside Iraq which, as Packer shows was not necessarily the hardest part.

Packer identifies himself as a liberal who supported the war not because of suspicions about Saddam’s weapons of mass destruction but because of his regime’s “fascist” nature.

Years before the war Packer came to know Kanan Makiya, an Iraqi exile intellectual whose writings inspired many supporters of the war. In Packer’s book Makiya becomes a good ghost haunting Iraq and, in the process providing the different reportages, some of which previously published in magazines, with a degree of thematic unity. Packer maintains his deep feelings for Makiya but remains undecided about the exiled intellectual’s “dreamlike” vision of a democratic Iraq. The scenes in which we see Makiya returning from liberated Baghdad to Boston, to a new house, and to exile, accompanied by his long lost love, an Iraqi lady he had abandoned back home decades ago, is truly heart-rending. The new house in Boston is being refurbished as Makiya and his sweetheart prepare for a second life in exile. It is as if even liberated Iraq could not offer someone like Makiya, with his dreams of democracy, a minimum of safety and dignity.

While Makiya looms as a larger than life character in this book, Packer introduces us to numerous other Iraqis along with American and British volunteers who are determined to stay and make the new Iraq a success. The impression created is that, although the media put the emphasis on suicide bombers and the remnants of the Ba’athist regime, Iraq is full of good people who believe that evil could, and should, be defeated. Packer was impressed by the work done by the people of Hillah, a Shiite city close to Baghdad, to come to grips with a tragic past and build a better future. But his most enthusiastic account is reserved for of Kirkuk a cosmopolitan city of Kurdish-Arab-Turcoman and Christian Assyrian and Chaldaean communities dating back to more than 2000 years. By reading Packer’s reportage those who have never been to Kirkuk would want to pack their bags and take the first plane there. And, ye, he warns that Kirkuk may well emerge as the most complex issue of politics in post-liberation Iraq.

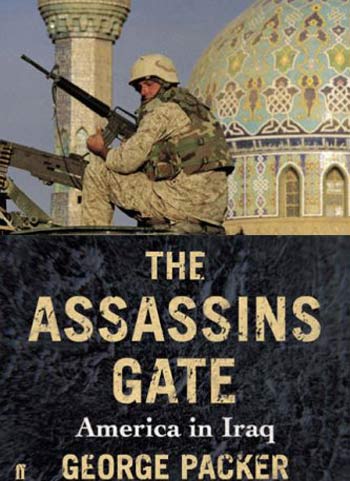

The “Assassins’ Gate” in Packer’s book refers to one of the entrances to the so-called “Green Zone” in Baghdad where the US-led coalition concentrated its administrative presence.

Packer claims that the names dates back to the medieval times. But this may well have been one of the many tall stories told him by his Iraqi guides and interpreters

The first part of Packer’s book could be read as a primer on the political zoology of American decision-making. He presents the arguments of both pro and anti-war camps with as much fairness as a “liberal” is capable of mastering. At times he seems obliged to repeat some old chestnuts, for example that the US liberated Iraq to please the Israeli Likud Party or to seize control of Iraqi oil. But in almost every case Packer, to his credit, is obviously unhappy about repeating those assertions.

The reader could, of course, ignore the commentary part of the book and , instead, focus on its reporting aspect. An excellent reporter, Packer emerges as one of the few- I only know two other- Western journalists who developed a real feel for Iraq and managed to communicate with the Iraqis at a deeper level. Packer’s reportages shows that the liberation was a necessary act, and that the majority of Iraqis are determined to build a better life. He also laments the fact that “no one wants to hear good news about Iraq.”

Although Packer still supports the war on balance, he is honest enough to express the doubts raised by opponents of the liberation from the start.

He writes: “Since America’s fate is now tied to Iraq’s, it might be years or even decades before the wisdom of the war can be finally judged…. Paul Wolfowitz and the war’s other grand theorists took the Longview of history; if they hadn’t there never would have been an American invasion of Iraq, or, at least, not nearly so soon.” Later he asks: “Who has the right to say whether it was worth it?”

It is clear that Packer admires Wolfowitz who was the number-one target of anti-war groups for years. (Earlier this year Wolfowitz abandoned his post as Deputy Defence Secretary to become President of the World Bank.) But this does not prevent Packer from criticising Wolfowitz for the handling of he post-war situation in Iraq

Packer shows that the United States is not designed to act as an imperial power, and reserves his strongest criticism for the way US politics works.

He writes: “America in the 21st century seemed politically too partisan, divided and small to manage something as vast as Iraq.”

Packer contrasts that with the determination of the Iraqis to defeat the terrorists and build a democracy. He quotes a young judge in Baghdad as saying: This is a battle, mister, and we’re all soldiers in this battle. So, there are only two choices-either to win the battle or to die.”