When President Muhammad Khatami’s Ministry of Islamic Guidance worked on the final list of banned writers and poets in the winter of 1997, few expected that Amir Ashiri’s name would be one of the 3000 or so “enemies of Islam and the Revolution” to be forbidden from publishing in Iran.

The reason was that Ashiri, a master of thrillers who has just died in Tehran aged 93, had always regarded himself as an “entertainer” whose aim was to give his readers “a few moments of distraction.”

Born in Tehran in 1923, Ashiri was one of few Iranian intellectuals of his generation not to be seduced by Marxism and its message of universal revolution that had started in Tsarist Russia in 1917. Nor had Ashiri flirted with the “Aryan” movement that preached the revival of the ancient Persian Empire and the rejection of Islam as an “alien Arab ideology.”

Ashiri shunned ideologies. He was, as he once told me, “just a story-teller”.

And, yet, in 1997 his name did appear on the Islamic black list because the ruling mullahs could not conceive of a literature that wasn’t in the service of an ideology.

Between 1947 when he published his first novel “Rites of Thunder” and 1979 when his last work “Smile in a Funeral” was published, Ashiri wrote more than fifty novels, all but two of them fast-paced thrillers with a wide readership.

From the 1930s onwards, many Iranian writers published their novels in the form of serial instalments in weekly magazines. Those serials attracted a large audience that would be lost to television two decades later. (The first TV appeared in Iran in 1955). People would rush to buy the latest edition of magazines such as “Tehran Musswar” (Tehran Illustrated), “Asia-e-Javan” (Young Asia) or “Tarraqi” (Progress) to find out what happened to protagonists in their favorite serials.

At some point in the early 1950s, Iran boasted more than 20 weeklies almost all of which ran serials. Some of those magazines sold more than 30,000 copies, a circulation number that is rare in Iran today.

Some serial writers became household names, among them Hosseinqoli Mosta’an who defied the patriarchal society by giving women the main roles in three of his most popular novels: “Shahrashub”, “Afat” and “Rabiah”. Others, like Jawad Fadel, adopted romantic themes that in some novels, for example “Yeganeh” (The One and the Only) , made schoolgirls cry under their duvets. Still others, for example Hamzeh Sardadwar, used history mixed with legend to tell part of the complex Iranian narrative.

In later years a younger generation, for example Sadreddin Elahi in his “Our City Blonde” used the serial as a roundabout method of social commentary, attracting a vast audience. In his “Whiplashes in Paradise”, Nasser Khodayar, a charismatic journalist and broadcaster, used the serial as a weapon against his former Communist comrades in a merciless ideological battle against Stalinism.

Other writers used the serial as a means of escaping the prevailing “real life” which, for many Iranians, was no bed of roses.

In terms of craftsmanship, Majid Dawami’s seemingly endless serials “Tooti” (Parrot) and “The Masked Man of Zayandehrud” were the best examples. Legend has it that at one point the Prime Minister of the day, unable to sleep without knowing what had happened in the serial, sent a special team to a printing house where the magazine running “The Masked Man of Zayandehrud” was printed to find out the next episode before the paper came out.

In that context, Ashiri was in a category of his own. He was the master of literature as escapism. He had no message, and didn’t even try to create three dimensional characters. In some cases his writing resembled comic strips in words. Those with intellectual pretentions never admitted they read Ashiri, although they did on the sly and, as some privately admitted, enjoyed it immensely.

Although there was at least one corpse in every one of his novels, Ashiri was not a writer of detective stories in the style of say Conan Doyle or Agatha Christie. Iranian detective literature had to wait for Esmail Fassih and his “Sharab Khaam” (Raw Wine) two decades later.Nor could he be categorized as a regular thriller writer in the style of say Ian Fleming or Eric Ambler.

Three factors gave Ashiri’s work, which in my opinion remains under-appreciated, its own cachet. The first was that he would imagine fantastic events in a context far removed from any conceivable version of the Iranian life in his time. He would then take an ordinary Iranian and place him at the center of those events. The circle would be rounded with an accurate, ultra-realistic description to the last detail of the venue of the events. In “ The Execution of an Iranian Youth in Germany”, for example, you have a hero who could be your neighbor in Tehran who somehow lands in Berlin to find himself entangled in a complicated intrigue with the Nazis.

Secondly, Ashiri had a natural gift for writing simple, fast-paced Persian, free of the poetical flourish and rococo ornamentation that made the writing of clean prose something of a challenge. He steered clear of adjectives and adverbs and in every case chose the simpler of any two words available to him. No roses, nightingales, moonlights, and sad violin tones for this hard-boiled master of cynical optimism.

Finally, he gave his characters more freedom than most of his contemporary novelists believed was wise. In some cases, the reader could feel that Ashiri himself was surprised by the out-of-character way that his characters behaved in certain circumstances.

Some of his thrillers, for example “The Blue-Eyed Spy” and “Satan’s Footprint” may have been inspired by the two-reel movie serials from Hollywood that were marketed in post-war Tehran with much success. But even then, the reader could see Ashiri’s unmistakable style at work.

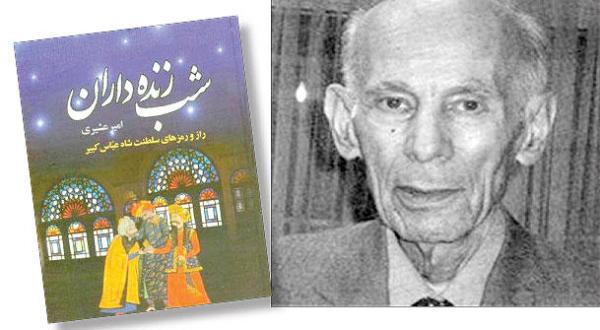

His longer novel “Portrait of a Murderer” starts like what the English call “the shilling-shocker” but develops into a more sophisticated portrayal of the Iranian society of his time. Another longer work “Siah-Khan” (The Black Chief) represented one of Ashiri’s two attempts at writing historic novels. (He also wrote a two-volume biography of the great Safavid king Shah Abbas).

In later years, many writers imitated Ashiri, among them R. Isfahani. But almost none came close. Perhaps, the only exception was Parviz Ghazi-Saeed who, had he had the time, might have gone even further, but was “shot down” during the Islamic Revolution.

There were times when Ashiri wrote four different serials in four different weeklies, among them “Roshanfekr” (Intellectual) “Sepid va Siah” (Black and White) and weekly “Ettelaat” (Information).

I met Ashiri in the 1960s when, as a teenager, I did a reporting stint with the weekly “Roshanfekr”. He always looked somehow wobbly, like a fragile sapling in the wind. But as things turned out, he has outlasted many of his contemporaries. Despite bring banned by the mullahs for decades and forced to live in relative penury, people still remember him, often with fondness. That is the blessing that literature bestows on its true servants.