For more than 30 years the Iranian press has had to observe a black list of names that should never be mentioned in print in the Islamic Republic. A good many of those “forbidden” names belong to pre-revolution film stars who were admired, criticized, loved and hated by millions of Iranian cinema-goers.

One of the first things the mullahs did when they seized power in 1979 was to shut the Iranian film industry which had found a slot in the global top-10, producing at least 40 feature films each year. Many stars and film-directors were sent to prison on trumped up charges. Some had their homes and bank accounts confiscated, their pension schemes scrapped, and forced to survive with help from family and friends.

Bearing the brunt of the repression were Iranian actresses who were regarded as doubly guilty because they were both women and played in films.

Thanks to the new media revolution, however, the pre-mullah cinema and its stars didn’t fade away. Millions of VHS tapes and DVDs of banned films have been sold on the black market, at times with the mullahs themselves buying some on the sly. Iranians still remember the stars that shone in their lives so many decades ago.

Bahman Maghsoudloo, one of Iran’s best-known cinema critics and historians, has decided to tell the story of the pre-revolution stars in a new documentary entitled “Razor’s Edge: The Legacy of Iranian Actresses”. The 90 minute-long film is the result of almost 20 years of titanic research, often in clandestine sorties under the nose of the secret police.

Although the film is built around interviews with 23 actresses it spans a wider scope to offer a quick narrative of the Iranian film industry which started in 1900 and produced its first “talkies” in 1932.

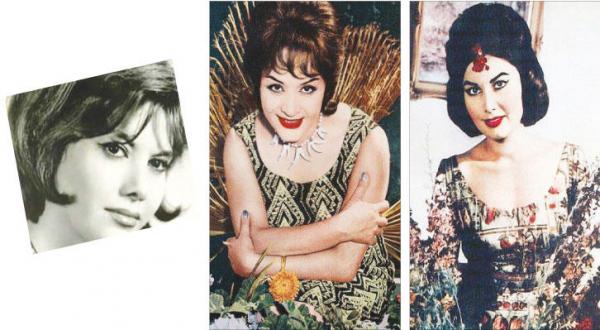

Among those interviewed are such box-office stars as Farzaneh Taidi, Irene Zazians, Shahla Riahi, Fakhri Khorvash, Pouri Banai and Vida Ghahremani. Some almost mythical actresses, for examples Loretta, make a cameo appearance.

As far as this cinephile is concerned only two great actresses are missing: Mahin Dayhim and Parkhideh. Also, I would have liked a bit more of Azar Shiva and Zhaleh Mohtasham (Olov).

However, the film contains a number of exciting surprises. One is the appearance of Shahrzad, the very symbol of what some intellectuals dismissed as “vulgar Persian cinema” aimed at unwashed and illiterate masses. Originally a cabaret dancer, Shahrzad, who says in the interview that she didn’t “go to college”, learned the ropes to become an accomplished actress. She then made history by becoming the first Iranian woman to write and direct a film “Maryam and Mani” in 1976, topping the box office while seducing the critics.

Another surprise comes from interviews with Irene Zazians and Shahla Riahi, both of them top stars in their time, depicting the working conditions of the Iranian cinema industry in the 1960s and ‘70s thus shedding light on a chunk of Iran’s contemporary history. Shahla Riahi had also directed a film “ Marjan” in which she played the title role.

Long interviews with Farzaneh Taidi and Vida Ghahremani reminds us that it was always difficult to be a woman in Iran even under the Shah, and that being a film actress was even more of a gamble.

Iranian women in cinema had to jump many hurdles. There was much agonizing on whether or not to show a woman smoking a cigarette, for example. Even worse torture was the debate over the first kiss in an Iranian film. That happened between Vida Ghahremani and Nasser Malek-Moti’ee, then the top male star of Iranian cinema, in the thriller “Crossroad of Accidents” directed by Samuel Khachikian. The brief scene created a national scandal. Vida’s husband forbade her to appear in any film for two years.

Farzaneh Taidi faced an even bigger threat. A provincial cousin whom she had never heard of appeared at her home in Tehran carrying a gun and tried to shoot her for dishonoring the family by playing in films. She ended up with a lesser punishment with her father beating her up with his belt to silence the family clamoring about lost honor.

While slapping women on the face was quite routine in Iranian cinema, having a woman slap a man was a big dilemma. However, that, too, happened in 1965, causing another national scandal with traditionalists complaining that having a woman slap a man could signal the end of the world.

Right from the start Iranian actresses didn’t wear the hijab that later became the symbol of Khomeinist rule. It was invented in the 1970s and imposed on Iranian women from 1982 onwards. However, actresses often wore a headscarf in the fashion of women in real life, especially in the countryside.

By the 1960s, however, even that had disappeared and speculation was rife about when a film star might appear in a swimsuit. That happened in 1964 when Irene Zazians, one of the most beautiful women to grace cinema anywhere, did just that.

The next challenge was when and how an Iranian film star would get undressed on screen. Specially targeted was Pouri Bana’i, another great beauty, who took the plunge in “Goodbye Tehran” another thriller by Khachikian.

Then years later, it was “Goodbye Cinema” for all the stars as the new regime consolidated its hold on Iran.