Since the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran in 1979, the Shi’a Islamist authorities in Tehran have gone to great lengths to carry the banner of the Islamic world. The trouble has so often been that other Islamist movements have either been reluctant to, or have simply rejected, any aspirations of the Iranian leadership. The reasons are manifold, but a couple of principal obstacles have stopped Iran’s Islamist rulers from being appealing to Islamists from other parts of the Islamic world.

As a non-Arab country, Iran always faced an uphill struggle to propagate its message to the Arab masses in particular. Tehran has had a few localized success stories, the most notable being its creation and preservation of the Shi’a Lebanese group Hezbollah, but Arab Islamists have largely chosen a path separate from its Iranian counterpart. The other key handicap for Iran, at least in the view of Sunni Arab Islamists, is the highly Shi’a-centric nature of the Iranian Islamist model. From the early days of Ayatollah Khomeini’s 1979 revolution, Arab Islamists saw Iran as a Persian and Shi’a power, and that reality has shackled Tehran’s global Islamist agenda ever since.

In the intervening years, Tehran’s fortunes with Sunni Arab Islamists have plunged further. The “Arab Spring” and its many manifestations—the most important of which being the bloody conflict in Syria—have squarely put Tehran on a collision course with Arab Islamists. The Muslim Brotherhood in Syria, part of the armed rebellion against the regime of Bashar Al-Assad, is in effect physically fighting Iran thanks to Tehran’s unwavering political and material support for the Assad regime. Iran’s support for Assad was even hard for Palestine’s Hamas to endure, leading to a rupture between the two sides that could prove irreparable.

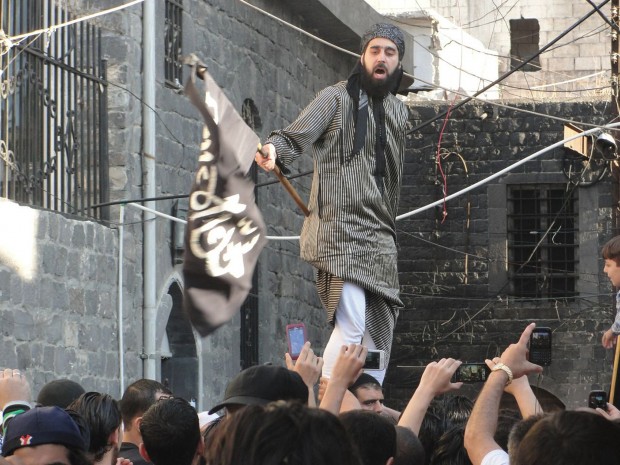

It is in the Syrian conflict where Iran faces both the biggest challenge and, perhaps, also a big opportunity. The challenge to Tehran comes because its Islamist credentials have largely been washed away, given that it is effectively backing a secular Assad regime against a multi-layered opposition that includes strong Islamist components. Nonetheless, it is also an opportunity, given that some of the most violent extremist jihadist groups in Syria are now not just battling it out against Iran, but are also enemies of some of Iran’s key rivals, including the United States, Saudi Arabia, and even Israel.

This shared antipathy toward violent jihadists is now openly touted in Tehran as a potential bridge between Iran and Saudi Arabia. This could well be the reason why Tehran could soon redouble its efforts to reach out to Riyadh. When accepting the credentials of the new Saudi ambassador to Tehran, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani said that “security relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran can help halt unrest in some regional countries and prevent the spread of sectarian violence in the region.” The Saudi envoy, Abdulrahman Bin Gharman Al-Shihri, reportedly responded positively, saying Riyadh is ready to expand ties with Tehran.

But for this outreach to be compelling, Tehran has to speak with one voice and in a more convincing manner. And here lies the challenge for President Rouhani, who has pledged to overturn Tehran’s old foreign policy. On March 2, Ali Akbar Velayati, the top foreign policy aide to Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, spoke about Muslim states keeping “vigilant against the divisive plots hatched by the enemies to create rifts among [Muslims].”

The suggestion, however, that all sectarian tensions among Muslims are fabricated by non-Muslim powers is a feeble one. As Velayati uttered those words about pan-Islamic solidarity, Iran’s security forces prevented a Sunni Iranian cleric, Moulavi Abdul Hameed, from participating in a conference of the Muslim World League in Mecca. Iran’s former president, Ayatollah Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, was more frank when he said that relations between Tehran and Riyadh have “never been this dark” and that the policies of both sides were to blame for this state of affairs.

Meanwhile, Iran’s idea of cooperation and a collective front against extremist jihadists does not need to only apply to Saudi Arabia and other Arab countries. In fact, both the United States and Israel are also targets of the same anti-Shi’a, anti-Western and anti-Jewish jihadists that are mortal enemies of Iran. But as is the case with Saudi Arabia, to be able to foster a common front against violent jihadists, the Iranians need to go back to the drawing board to rethink their foreign policy and security priorities. Some analysts and policymakers are already quietly making the point that the long-term security threat to Shi’ite-majority Iran is not the United States or even Israel, but non-state extremist jihadist groups with nothing but venom for all things Shi’a or Iranian.

The counterpoint to this article can be read here.