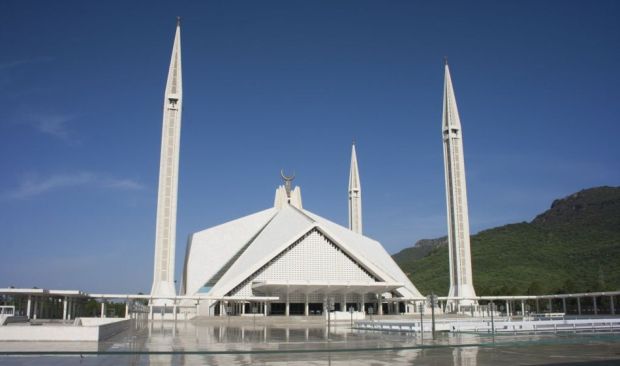

File photo of King Faisal Mosque in Islamabad. (Asharq Al-Awsat)

Islamabad, Asharq Al-Awsat—Saudi Crown Prince Salman Bin Abdulaziz Al Saud’s visit to Pakistan—the first stop on his current tour of Asia—was an expression of Islamabad’s importance as a close ally of the Kingdom for over six decades, confirming its pivotal role in the region.

Pakistan’s reception of the Crown Prince was remarkable. Aside from the usual reception procedures and state banquets, the agenda was full of high-level meetings with senior Pakistani officials and the signings of a number of agreements. Pakistani officials also expressed significant gratitude to King Abdullah for the relief the Kingdom provided to the victims of the earthquake that hit Pakistan in 2005.

Saudi–Pakistani relations are truly interesting, particularly to Western analysts and observers. Relations between the two countries go beyond normal levels, and that is reflected in a number of different fields. There are more than 2 million Pakistani migrant workers in Saudi Arabia. The commercial exchange between the two countries reached 111 billion Saudi riyals (29.5 billion US dollars) between 2003 and 2012, reaching a peak of 16.3 billion Saudi riyals (4.3 billion US dollars). At the lowest point during this period, 2003, commercial exchange stood at 4.2 billion Saudi riyals (1.1 billion US dollars), according to an economic report produced by the Al-Eqtisadiah newspaper.

More than this, there has also been an excellent level of military cooperation between Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, particularly in training military personnel. As part of the reciprocal military cooperation between Riyadh and Islamabad, more than 1,200 Pakistani training officers are operating in different military and security sectors in Saudi Arabia. There are also Pakistani training officers working with the security apparatus affiliated to the Saudi Interior Ministry, and others working within the armed forces sector.

And this historic relationship between Saudi Arabia and Pakistan is not limited to the military and economic sectors; it covers a number of other fields.

But what distinguishes the relationship between the two countries, particularly these days, is their shared political vision on a number of issues in spite of the various transformative political phases Pakistan has passed through since 1947. One can say that the shared mutual interests between the two countries have remained the same. Saudi Arabia views Pakistan as its strategic depth in Asia. At the same time, Islamabad views Saudi Arabia as the most significant Islamic country in the Arab Gulf; Saudi Arabia is its gateway to the Arab world.

For this reason, the firm relationship between Riyadh and Islamabad becomes the subject of speculation and rumors every now and then, with false stories circulating in the Western press every time officials from the two countries exchange visits.

During this visit, every military figure I spoke to referred to two historic moments in the history of the relationship between Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. One official affirmed that these two incidents live long in the memory of the people and government of Pakistan.

One Pakistani military official explained: “In 1998, when we defended our right to possess nuclear weapons and establish a strategic balance after our neighbors in India tested their nuclear bombs on May 11 and 13, 1998, we were abandoned by everyone except Saudi Arabia. The Kingdom stood with us and supported our right to possess these strategic weapons. Then, when we were military exposed, Saudi Arabia helped us—after we were abandoned by the Soviet Union.”

It is not difficult for visitors to Pakistan to notice the structural economic problems that have been accumulating over the past decades. In light of the political and security situation in Pakistan over the past few years, these problems have only been exacerbated and complicated.

Nevertheless, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has confirmed that Pakistan’s economy has started to show signs of recovery, thanks to the reformative steps taken by Nawaz Sharif’s government. This has been reiterated by the country’s Minister of Finance, Ishaq Dar, who stressed that his government’s reformative agenda is bearing fruit, with the economy enjoying 0.5 percent growth in the first quarter of the current financial year. The Pakistan Central Bank has predicted that the country’s economy will achieve a growth rate of four percent in 2013–2014, an increase from the 3.6 percent growth rate recorded in the 2012–2013 financial year.

At Nur Khan Airbase

The Crown Prince’s plane landed at Nur Khan Airbase at around 6:00 am local time. Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif received the Saudi Crown Prince and the accompanying delegation in a spirit of warmth and friendship. When the Crown Prince stepped off the plane there was a 21-gun salute, and then the Saudi and Pakistani national anthems were played as the Crown Prince reviewed the honor guard and shook hands with a number of senior Pakistani officials, including the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Gen. Rashad Mahmood.

The weather was warmer than expected. The road from the airbase to Punjab House, where the Crown Prince and the Saudi delegation were staying, was expected to be empty, but both sides of the street were adorned with portraits of the Saudi Crown Prince and the Pakistani president.

Punjab House Palace is a beautiful, elegant building designed by well-known Pakistani architect Nayyar Ali Dada. Born Nayyar Ali Zaidi in 1943, Dada is considered one of Asia’s most prominent architects. The palace is located in a green area in the northern part of Islamabad. Distinguished by its white colour and symmetrical, elegant lines, the palace overlooks vast green swathes of the northern parts of this young and modern capital city.

Negotiations with the Taliban

Islamabad is holding difficult negotiations with the Taliban. On Wednesday, the Taliban offered a ceasefire aimed at resuming the stalled peace talks in exchange for guarantees that the Pakistani army would not attack its positions.

On Monday, the government suspended talks with the insurgents after a Taliban-affiliated militia claimed the killing of 23 Pakistani soldiers kidnapped in June 2010. Islamabad immediately ordered the suspension of talks with the Taliban.

Since Sharif launched the peace process in late January, at least 70 Pakistanis have been killed in attacks by Taliban.

As a condition for peace, the Pakistani Taliban is demanding the release of members who are currently detained, the army’s withdrawal from the tribal regions—a stronghold for the Taliban and Al-Qaeda in northwestern Pakistan—and the imposition of its interpretation of Islamic Shari’a Law. Some of these demands are unacceptable in the eyes of the Pakistani government and military establishment.

Furthermore, the prospect of a US withdrawal from Afghanistan has created an oppressive atmosphere at the negotiations that may push them to failure. Despite the resumption of talks, few observers are optimistic about their success.

The Ahmadiyya File

The jihadist issue in Pakistan has its roots and repercussions, particularly in the border areas.

In her 2008 book, Partisans of Allah: Jihad in South Asia, Ayesha Jalal deals with the large-scale protests help by people calling for the Ahmadis to be declared non-Muslims. The Ahmadiyya sect was founded by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad in the 19th century; that is to say, a long time before the establishment of Pakistan. The protestors aimed in part to create a state of turmoil within the federal government of Pakistan by demanding the resignation of then man who was then Pakistan’s foreign minister, an Ahmadi called Muhammad Zafrulla.

In that tense atmosphere, two federal judges issued a security report warning of the destructive ideologies emerging in the fledgling country.

Their findings, known as the Munir report, appealed to the government to refrain from declaring Ahmadis as non-Muslims. They warned that the government having the right to determine who is Muslim and who is not would encourage takfirism and calls for partition in a manner that contradicted Pakistani founder Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s vision of a unified country.

“The result of this part of inquiry, however, has been anything but satisfactory, and if considerable confusion exists in the minds of our ulama [religious scholars] on such a simple matter, one can easily imagine what the differences on more complicated matters will be . . . Keeping in view the several different definitions given by the ulama, need we make any comment except that no two learned divines are agreed on this fundamental [principle]. If we attempt our own definition, as each learned divine has done, and that definition differs from those given by all others, we unanimously go out of the fold of Islam. And if we adopt the definition given by any one of the ulama, we remain Muslims according to the view of that alim [religious scholar], but kafirs [unbelievers] according to the definitions of everyone else,” the report said.

In a similar case following the first presidential elections in Pakistan in 1965—in Muhammad Ayub Khan’s era—Khan’s allies tried to weaken and damage the reputation of his main rival, Fatimah Jinnah. They attacked Jinnah, the sister of Pakistan’s founder, by issuing a fatwa banning the appointment of a woman as president. This same claim was repeated decades later when Benazir Bhutto became the country’s first female prime minister.

Attempts to use Islam as a tool to delegitimize certain political actors or organizations—whether the Ahmadis or others—have led to the emergence of terrible and lethal ideological currents in Pakistan, encouraging the phenomenon of takfirism and extremists using violence to kill anyone they view as being infidels.

I believe this Foreign Minister of Pakistan, Zafrulla Khan, that you mention, Muhammad Zafrulla Khan, who was a Ahmadi Muslim, and later become chairman of Gen Assembly UN and Presiding Judge at the World Court Hague, was instrumental in championing the rights of the emerging Arab states in 40-60’s. He was a classical Arabic scholar too, having translated Riyahh as – Salihin of Imam Nawawi and a English translation of Holy Quran.

King Faisal invited him to Arabia as his personal guest.