Cairo, Asharq Al-Awsat—It was family friend Mohamed El-Baradei who first told Hazem El-Beblawi he had been chosen to become Egypt’s new prime minister. It was a dangerous time for the country: Islamist president Mohamed Mursi had just been ousted by the army (headed by then-Gen. Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi), violent clashes were being reported daily, and Muslim Brotherhood supporters were still camped out in huge numbers in Cairo’s Rabaa Al-Adawiya and Al-Nahda squares. Baradei promptly informed Beblawi he was being summoned to the presidential palace to meet interim president Adly Mansour.

However, his stint as prime minister was brief, and the cabinet was dissolved by Mansour in February 2014, with Beblawi largely shouldering blame for the government not being able to fix the country’s myriad economic problems.

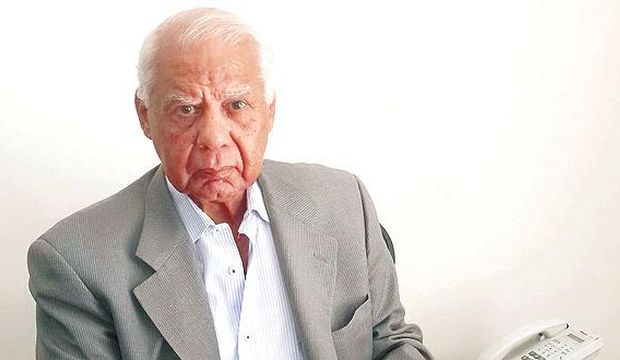

Seventy-seven-year-old Beblawi is, by training, an economist, not a politician, and holds a PhD in Economics from the Sorbonne University in Paris. He began his academic career teaching at the Faculty of Law at Alexandria University in 1965, later teaching courses at the University of Southern California and in Kuwait. He has also authored several books including The Rentier State with Giacomo Luciani and a book on the economies of the Gulf states, and worked at regional financial institutions such as the Arab Monetary Fund and the Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development.

After Egypt’s revolution in 2011, he joined the new interim government, first as an adviser to the government and then as minister of finance, before briefly leading the government himself following Mursi’s ouster.

In the first of this two-part interview, he talks to Asharq Al-Awsat about his long, distinguished career, his memories of ex-presidents Gamal Abdel Nasser and Anwar Sadat, and his own turbulent time in office.

Asharq Al-Awsat: You became prime minister at a decisive moment in Egypt’s history. When did you realize that you were going to be appointed to this office?

Hazem El-Beblawi: I had no idea, but as in similar matters, names were suggested for a post, and my name was among those which were reported after July 3 [Mohamed Mursi’s ouster]. I had no contacts or any information, but I also cannot say I was totally surprised. I can’t say that I would have been disappointed had I not been chosen; no, not at all. But I knew then that there were seven or eight names being considered for the premiership, and that my name was among them.

Q: Did you imagine when you were young that you would become prime minister?

In childhood, there are too many simple ideas which do not count, and no one knows where those ideas will take them. However, once I reached a certain level of education, knowledge and responsibility, I became aware that I wanted to play a public role, but not necessarily in politics. For instance, I wanted to play a role in the literary field and in economics. I also wanted to contribute to the public dialogue, but it never crossed my mind to practice politics. In the preparatory and secondary school stages, I was a diligent and high-achieving student, and I played football and other sports with my friends.

That period at school when I became conscious of events around me was before and after the 1952 revolution. During that period, Egypt was going through a wave of events and political parties, including the Wafd Party, the Muslim Brotherhood, and the Young Egypt Party. Then the revolution came when I was in my final year in secondary school. At the time I was interested, because the idea was that the regime had crossed the line and change was needed, and therefore everybody welcomed the revolution.

But during the period which followed—the power struggle began between late presidents Muhammad Naguib and Gamal Abdel Nasser—I was on Naguib’s side on the basis that he represented the revolution and his leanings were more civilian. Then things changed after the 1956 Tripartite Aggression [Suez Crisis], with total support for Nasser.

Q: When did you first hear about the Muslim Brotherhood?

When I was in secondary school.

Q: Did you interact with them at the time?

No, some of my friends did. I was never close to them or ever sympathized with them. However, from an early stage, and this was when I enrolled in law school, I was certain that my political leanings were totally civilian, supporting public liberties.

At the start, I leaned towards the leftist tends, and then there was a type of balance appearing between public liberties and economic freedoms and others. While I was studying at Law School, and despite the fact that I was happy with the revolution, [namely] that time just before the nationalization of the Suez Canal and the Tripartite Aggression, I was concerned that the country would fall under military rule. Not only that, but at the same time, there were demonstrations which claimed the Free Officers’ Movement was supported by the United States.

That was turned upside down in 1956 when Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal and the vision [he offered] was building a new free and independent state, and this continued until the 1967 [Six-Day] war.

Q: Where were you when this war took place?

I was teaching at Alexandria University and I was delegated to the office of a government minister too, which was when I returned from a scholarship abroad. I still think the 1967 war was the biggest shock that my generation faced. I think what took place felt like total deception. We used to see Egypt as much more powerful militarily, and were surprised that we had [made] no preparation or [increased] readiness, and that there were exaggerations made in the early days [of the war], like claims that Egypt had downed 30 or 40 Israeli jets.

I think this was the biggest event to affect my generation, because after 1956, we felt we could match anyone in the world and impose our will on them, but it turned out to be empty talk more than anything else. I think this was a defining moment, not only in my personal life, but in the Arab world and the history of the region. Israel was established in 1948, but it did not become a reality until 1967 . . . In [global] public opinion and in Jewish society, there was no certainty that Israel would survive as a state. The view of Jews was divided regarding the Israel, and whether this project itself was sane or insane; and that continued until 1967. In fact, this was a defining moment in my personal life and my vision, and I believed that even if the leader was devoted and serious, the lack of democracy and an opposition were sure to cause great problems. I felt that the defeat was a result of absolute rule, lack of information, and the spread of lies.

Q: Where did you learn the truth about what happened in 1967?

I was delegated to the then-planning minister, Labib Shaqir, at the time, and I used to travel from Alexandria to Cairo two days a week. The day of the Israeli attack on Egypt, June 5, which was a Monday, I went to the Ministry and as usual, it was bustling. There were people saying we downed Israeli aircraft and some were praising God and saying, “We downed 30 aircraft.” I was in the minister’s office then with one of his advisers. He phoned the interior minister, Shaarawi Goma, then put the phone down and said: “Our aircraft are pounding Tel Aviv right now.”

That night, I returned to Alexandria and there, I listened to different radio stations. I was shocked by the catastrophe. I can tell you that all dark thoughts which could run through someone’s mind took over mine on that day.

A few months later, I traveled abroad for a short trip, but I felt that life was unbearable, not only because of the defeat, but because of the lies and the shame. I did not feel that things were improving until after 1973, because this time, everything was based on evaluation, preparation, and scientific planning, not a foolish rush.

Q: But how did you feel when President Anwar Sadat talked about launching a war to take back Sinai without carrying it out, two years before the actual war?

I was hopeful. The time between 1967 and 1973 may not have been long, but to my generation, it seemed like an eternity. We were unable to take any more. It seemed like 100 years of disappointment. But after that, when Sadat talked about liberating Sinai in 1971 and 1972, I used to wish that would happen, but when he talked about the “fog” which prevented this operation, I felt deeply disappointed. I said: “Here we are repeating the same talk, nothing but talk again.”

However, after that, when I realized what was going on, I saw that Sadat was farsighted, because at the time, the issue was not one of a lack of arms. He wanted the war to become an international issue. What he had meant by “fog” was the atmosphere of war between Pakistan and India which dominated the global media, while Sadat wanted that war to end first, to prepare the international ground for the Egyptian war. Had the war taken place in 1972, Sadat would not have received the international attention he desired. Therefore, I think Sadat was one of Egypt’s great men, even if I did not forgive him many minor mistakes, which most people commit.

Q: Sadat was preparing for peace with Israel. What were your thoughts for the future as you saw this trend emerging?

One needs to be realistic. The direction which Egypt took at that time was to solve the problem totally and to confront your enemy with all your tools: military, diplomatic, public opinion, and so on. I think Arabs and Palestinians missed a historic opportunity when they rejected Sadat’s invitation to Mena House [a hotel near the pyramids where the peace talks were held], when there were flags for all delegations including the Palestinian delegation. Things began to worsen for Egypt, so it had to work on peace with Israel, and I think in the end you cannot get what you want, only what [it is possible] to get.

Q: There were also objections inside Egypt, and also at your university. Did you expect a clash with Sadat?

Like every defining period when vital decisions are made, it is necessary that there are no differences in opinion. For instance, the opinions of the intellectuals were divided; even senior intellectuals like Naguib Mahfouz and Tawfiq Al-Hakim, they were not in agreement. I used to think that Sadat generally went the right way, but he was met with a lack of understanding from the Arab world, so he felt he had to take a different route. Had they understood what he wanted, they would not have forced him to take the path he did. The biggest losers in this were the Arab states which took this position against Sadat. Also, Egypt did not achieve all its aspirations, but it lost the least. The reconstruction started by Egypt in 1974–1975, including the restoration of the Suez Canal and attracting investment. Imagine if all that was still suspended; everything related to construction and development would have also been suspended until now.

Q: What are your thoughts on Sadat’s economic policies which he adopted after the war, including the lifting of bread subsidies?

The policies were right in principle, and the whole world was moving in that direction. However, it is fair to say that such measures needed more clarification. At the time, the world was divided between two camps: an Eastern camp lead by the Soviet Union, and a Western camp led by the United States. Egypt at the time, and until 1973, was in the Eastern camp.

Sadat made decisions which were farsighted, regardless of whether they were accepted or not. The wisdom is to know which direction the current is flowing, and he realized at an early stage that the socialist camp did not have long left, and he left it at the right time before he had to leave a sinking ship.

I think his basic choices were correct, including on the need for a free market economy, which does not mean that the state abandons its commitments. One of the main principles of a free market economy is for the state to be strong and be above everyone else, and to be able to stop market deviations, such as monopolies, and intervene in economic crises. I remember that Sadat’s basic choices were correct but they were not implemented correctly.

Do not forget that this coincided with his declaration that the state cannot exist under a one-party system, despite the fact that the country at the time had a dominant feeling that party politics was corrupt and pluralism was equal to division; but when the door was opened to pluralism, it was not opened in the desired manner.

Q: Do you think Sadat left problems behind for Hosni Mubarak, which proved a burden for the new president, and which needed resolving?

No. Mubarak followed Sadat’s course and completed his project. However, Sadat was able to create and innovate; Mubarak followed the same course without having a vision for development.

Q: But in the 1980s, Mubarak began to take practical measures for political pluralism, and in terms of the economy, he began to move away from the socialist policies inherited from Nasser . . .

These of course were good polices, but what destroyed all that was the fact that there was a need for basic guarantees. This is the fundamental mistake that Mubarak made. As for political pluralism, this is also good, but was the National Democratic Party [Mubarak’s party] based on selecting people who believed in his [Mubarak’s] ideas, or were they brought in to be used in return for the political advantages they offered? The important issue is that Sadat was innovative, took initiatives and made mistakes, but Mubarak was not innovative and followed the same course, and his performances were weak.

Q: Did you advise the government during the Mubarak era?

When Mubarak took office I was head of the Export Bank. Because of this post and my reputation in economics, I used to participate in some of the government’s Economic Committee meetings. I joined the UN in 1995, and in the last 10 years [of Mubarak’s rule] I attended the meetings of the government’s Economic Committee, but my attendance became less frequent due to my travels abroad. I left the UN in 2000 and started working abroad again for 10 years as a consultant for the Arab Monetary Fund. My links with life in Egypt were maintained through my articles on economics in newspapers, until the January 25, 2011 revolution.

When the protesters in Tahrir Square presented the names of their candidates for ministerial positions to from the first post-revolution government, my name was on the list. When I was officially asked to join the government, I agreed and took the post of finance minister. About a year and a half after I left the ministry, I found my name mentioned in connection with the post of prime minister. I was hesitant due to the circumstances in the country which followed the 30 June [2013] revolution [against Mursi].

Q: Who was the first person who told you about your selection for the post of prime minister?

[Mohamed] El-Baradei, who was vice-president at the time.

Q: Did you know him personally before that?

I knew him in a normal way, especially that he spent most of his time abroad and I worked abroad for many years too. We had meetings which were infrequent, but there was an old relationship as his father was a friend of mine and our families knew each other. We spent the last 30 years abroad but there is mutual respect and appreciation for one another.

When he called me about the premiership, my initial reaction was to apologize and reject it, and I said to him the security situation was unstable and the country did not need an economist, but a security figure.

I also told him that I wished they would bring in someone with a background in security to run the government, and that I would work with him on the economy, because the main problem which faced Egyptians at that stage was a security problem. The next day, Baradei called me again and this time I found that the issue was not about economy or security; the issue was that the country was in grave danger and we needed to do our duty for our country.

Q: When you went to meet former interim president Adly Mansour to be officially tasked with forming the government, did you have any conditions regarding the government program or the choice of ministers?

No. He told me I had complete freedom and I told him I had one request: I said to him, “You are a judge and you know the judiciary better than me, so can you recommend a minister of justice for me?” And he did.

Q: When, after being asked to form the government, did you first meet the then-defense minister and current President Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi,

I met him the day we took the oath at the Presidential Palace. I selected him without speaking to him because I knew him well since he was a member of the Military Council, when we used to see each other in meetings when I was a minister in the previous government. He was head of military intelligence at the time and it was natural for Sisi, who was a minister in the last government, to be part of the new government. So when I wrote down the names of the new ministers, I wrote his name.

Q: Did any official or organization instruct you to include Sisi’s name?

No one told me what I should do, but you know that I had an idea of what was going on.

Q: What about the other ministers, how were they chosen?

Of course I did not know everyone, especially having worked abroad for so many years. Therefore, I consulted others because I was not prepared to form a government and things were moving so fast. At the end of the day, I was the one who chose the ministers, including selecting an interior minister to continue working in the new government.

There are issues which were clear to me; there are national security posts, not just a defense minister, but also a minister of military production, minister of aviation, and interior minister. You cannot tell me that I have enough knowledge of the men of the armed forces and who among them would have been good for a ministerial post and who was not. This is called good assessment, and even then I can stress that I was not under any political pressure to select one person or another.

Q: Some people see the events in the Arab region, especially Libya and the emergence of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), as a conspiracy. Do you support this theory?

I do not support the idea of a conspiracy because there is not only one conspiracy, there are a thousand conspiracies. Conspiracies clash and the problem in a conspiracy is that people think of a reason for one conspiracy and another and waste time talking about them, instead of thinking about what to do to confront them. This is like someone is suffering from an illness, but then all the others do is say, “This person is suffering from such-and-such a virus,” instead of looking for a medic to help save them.

This interview was originally conducted in Arabic. The second part of this interview can be read here.