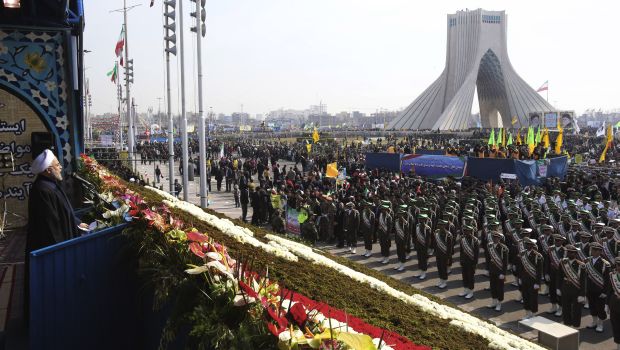

Every year since 1980, Iranians have held an annual celebration of Ayatollah Khomeini’s 1979 revolution. However, with the passage of time the number of Iranians who reject the revolution and believe it was the worst historical setback in the history of their country has increased. Year after year, more politicians and intellectuals who were involved in the revolution or supported it are re-evaluating the experience within the context of restoring consciousness—an act which usually follows revolutions or failed changes.

Today, as the Iranian Islamic Republic celebrates the 36th anniversary of toppling the Shah, another prominent Iranian figure has joined the ranks of those who speak out against the revolution: Mohsen Sazegara, who participated in establishing the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, which were and still are the military elite of the revolution and remain the most powerful and influential force in the country. Sazegara said, regretfully, that if he had the chance go back in time he would not have participated in the revolution, adding that toppling the Shah’s regime was a mistake which Iranians have paid too high a price for. Most of those who have changed their minds about the revolution are like Sazegara—retirees no longer seeking high-ranking posts and who are not part of the current political struggle. They are simply mature individuals who can observe the entire scene and evaluate it based on their experience and according to the end result of Iran’s current situation.

Any fair-minded historian will certainly agree that there were many defects and failures during the Shah’s rule. But the Shah—until the collapse of his regime in the 1970s—managed to turn Iran into one of the most developed and successful countries in the Middle East—compared to the Gulf, Egypt, and Turkey, for example. He transformed the country into an industrial and military power and a top regional scientific hub, making other countries in the Middle East regard Tehran with both envy and admiration. However, revolutionary zealots, from the leftist movement to extremist Islamists, deleted most of this history and rewrote it like Chairman Mao did in China and the Bolsheviks in Russia.

To confront this growing nostalgia for the Shah’s era, those who believe in the revolution and seek to defend it no longer try to forge recent history. This no longer works, because people’s memories of have been revived and millions of people who lived through the Shah’s era are actually still alive.

Their only option is thus to concoct excuses for the failures of the past 36 years in numerous areas including development, living conditions and individual freedoms. The remaining revolutionaries blame the West and the “hypocrites”—that is, the opposition—for their own failure.

But these excuses are no longer convincing. At the same time the regime seeks to reassure its audience at home of its negotiations with the West and that it is about to reconcile with some of its longtime rivals, many in the country will remember how a more secure livelihood and independence from the West—alongside calls for freedom and democracy—were the main slogans chanted by protesters calling for the downfall of the Shah in Tehran and its public squares.

Today, three and a half decades on, none of these demands have been met. The circumstances of Iranians today are actually worse than they were during the Shah’s reign. The margin of political freedom has decreased and social restrictions predominate. Parliamentary and presidential elections have been limited to Islamists, rivals have been jailed, and the only parties active are those affiliated with the regime. The situation is thus worse than it was when the Shah was around. Living standards have declined, misery reigns, and Tehran and the rest of Iran’s major cities have deteriorated into mere shadows of their former resplendent selves during the time of the Shah. After a long time on the revolutionary path, the political regime of the velayat-e faqih (Rule by an Islamic jurist) has turned its back on all its revolutionary slogans by seeking relations with its main enemy the United States. Not only that, the regime wants the US Treasury to allow it to exchange Iranian rials for US dollars, to allow people to remit money to Iran, and for the US Congress to allow Iran to acquire new technology for oil exploration and production.

Practically speaking, the revolution no longer exists in Iran. In its place we have just another repressive regime, with a political system and security services much crueler than the Shah’s. The only hope which the government and the Iranians have left is to achieve reconciliation with the West and become open to the world, just like Vietnam, Cuba, China and Russia did before them.